Originally published at: http://statelyplay.com/2017/09/15/cardboard-critique-navegador/

Tabletop •

I assume that board game publishers commission board game cover art to be evocative of the game’s theme while also creating some excitement for what lies inside that cardboard box. All publishers except PD Verlag, that is. Instead of promising a thrilling adventure, their box covers depict old white guys looking like they need to use the toilet. They broke new ground with Concordia, not only by having the cover focus on a woman instead of a man, but simply by depicting someone smiling and not looking like they’re waiting for the reaper to mercifully end it all. Today we’re looking back at one of Mac Gerdts’ better designs, Navegador, complete with a box cover depicting a sullen Henry the Navigator staring a map. Prepare thyselves for adventure!

If you’ve been paying attention to my previous Cardboard Critiques, you’ll be familiar with Navegador’s designer, Mac Gerdts. This is the genius behind one of my favorite games, Imperial, which also has a cover with surly gents looking at a map. While PD Verlag doesn’t have a great track record for box art, they make up for it with the art and bits inside the game, not to mention fantastic gameplay.

[caption id=“attachment_2933” align=“aligncenter” width=“841”]

Calm down, Henry.[/caption]Navegador is a game of exploration and economics based on Portuguese expansion in the 15th century. This involves founding colonies as your ships circumnavigate Africa and make their way to Japan and also building up your infrastructure in Lisbon so you can convert exploited goods into finished products. The hook making Navegador great is the fact you can’t do everything, and most of your decisions rely on what your opponents are doing. Like many euros, there’s no direct interaction with your peers but Navegador is most definitely not multiplayer solitaire and a winning strategy involves taking advantage of your opponents’ decisions.

This push-pull between players exists due to Navegador’s most important mechanism, the Market. Here, the three goods available–gold, sugar, and spice–are traded. When raw goods are sold, the Market becomes flooded and the price goes down. When factories process raw goods, the amount of goods available drops, forcing the price to rise. It’s basic supply and demand economics, but you need to stay on top of who is producing what and who has factories ready to grind those goods into finished products. If the person to your right is producing a lot of sugar, it would behoove you to build sugar factories so that when he floods the market with goods, you can profit the most. Of course, they love the fact that you’re processing their goods because that raises the prices next time it comes around to their turn. Of course, someone to your left could start producing sugar as well, dropping the price before it gets back to the original sugar producing opponent, and someone else could build sugar factories jumping ahead of you to process the sugar at high prices. There’s no mechanism that specifically forces players to stick it to each other, but opportunities naturally arise that will put a dagger in your hand, ready to slide into someone’s back.

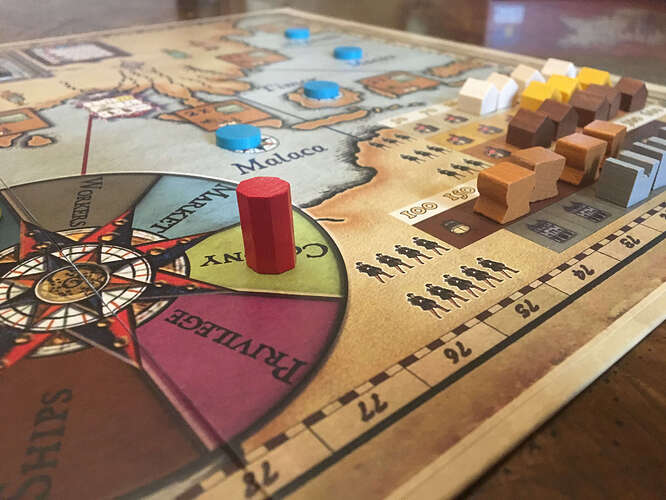

[caption id=“attachment_2997” align=“aligncenter” width=“4032”]

Oh, sweet rondel. I’ve missed you.[/caption]Like most of Mac Gerdts’ titles, Navegador uses a rondel, or a circular path filled with actions. You move a piece around the circle clockwise, each turn choosing one of three free actions you can take. Thus, you might want to buy a factory to take advantage of that sugar, but are too far away this turn to make it happen. I’ve played a lot of euro games and I’m starting to think that the rondel is my favorite game mechanism. Not only does it make teaching the game incredibly easy, but it limits what each player has to think about each turn, minimizing analysis paralysis and downtime between turns.

Unlike most economic games, but like most Mac Gerdts’ games, the winner is not the only with the most cash at the end of the game. Instead, Victory Points are scored at the end of the game by multiplying your achievements by a modifier that can be increased as the game progresses by currying favor with the Portuguese nobility. Each of your colonies is worth 1 VP at game’s end unless you bump up that multiplier, which can push it up to 4 VP each. The number of these privileges are limited, so stealing them before another player who’s focusing on a specific strategy is another great way to make your friends hate you.

[caption id=“attachment_2998” align=“aligncenter” width=“4032”]

Eastward, Ho![/caption]Navegador is a brilliant euro with very little in terms of luck. The only hidden information in the game is in the value of colonies as you explore with your ships, but the range of a colony’s worth is known before game time, so calling it an “unknown” is a bit of a misnomer. Navegador is a game of watching your opponents and profiting on what the other players are doing, reaping what others have sown. Navegador’s only fault lies with its theme of European trading in the Middle Ages/Renaissance, which has become something of a euro game trope. It doesn’t quite rise to the brilliance of Imperial, but it also plays shorter and is easier to explain to new players. If you’re looking for a Mac Gerdts game but don’t have the time or energy to teach Imperial, Navegador is a pretty great substitute.

If you’re interested in playing Navegador before rushing out and picking up a physical copy (and you should, using our link below), the game is available at Yucata, an online browser-based board game site. You can download the rules here, which should help you get up and running.